A "European" victory?

You would not have guessed it from the blizzard of blue and gold flags at the K Club in County Kildare today that the Ryder Cup was originally a sporting event between the best American professionals and those of Great Britain. The first contest was in June 1927 at the Worcester Country Club, Massachusetts, when the United States team defeated their counterparts from Great Britain 9½ -2½.

This victory was to set something of a precedent in that in the first 19 matches (played every other year, with none during WWII) from 1927 to 1971, the British won only three times and drew once – in 1969.

In an attempt to balance up this uneven competition, Ireland was officially added to the British team in 1973, it becoming an Anglo-Irish team for the three tournaments of 1973, 1975 and 1977. The addition, however, did nothing to change the fortunes of the players on this side of the pond. The US also won those three contests.

Almost in desperation, therefore, the British Professional Golf Association prevailed on its American counterpart to widen out the competition to all of continental Europe and, in 1979 the first of the modern matches was played, styled as the USA versus Europe. The US won that and the next two matches.

Meanwhile, the great dream of a "European identity" was stirring in the bosom of the nascent European Union (yet to acquire that name) and, in 1984 the European Council at Fontainebleau (where Thatcher got "her money back") commissioned a report from a committee chaired by Italian MEP Pietro Adonnino to recommend various measures to build the public's sense of European identity.

He reported back at the Milan Council in 1985, suggesting, amongst other things, a Euro lottery, an EU driving license, the adoption of the blue flag with gold stars; and the creation of European sports teams.

The latter endeavour has been singularly unsuccessful to the extent that when Romano Prodi in 1999 suggested "European" teams should represent the 25 EU nations at the Olympics, he was laughed out of court. But, ironically, the one area where the commission has had some success is in hijacking the "European" Ryder Cup, flooding the venues with its emblem.

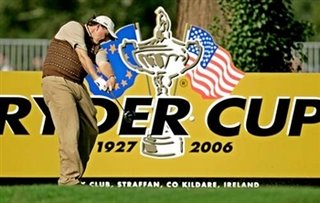

Thus, as the headlines proclaimed, "Europe wins historic third victory in succession over America in Ryder Cup", there were "ring of stars" symbols everywhere, on hats, scoreboards, flags, shirts, etc. All the television symbols and other publicity logos were blue with the ring of stars.

Thus, as the headlines proclaimed, "Europe wins historic third victory in succession over America in Ryder Cup", there were "ring of stars" symbols everywhere, on hats, scoreboards, flags, shirts, etc. All the television symbols and other publicity logos were blue with the ring of stars.This was all that Adonnino could have wanted when he proclaimed in 1985 that sport provided a key opportunity to promote a "sense of a European identity".

But, like so many things the EU touches, the victory was an illusion. The victorious "Europe" team included two Swedes (one of whom lost in the final day singles), two Spaniards (one of whom lost), two Irishmen (one of whom lost, the other ended all square) along with six citizens of the UK (four English, one Scot, one Northern Irish), all of whom won. In all, 21 of the 25 "European" nations were not represented. There were not many Latvians in view, or Italians, or French.

Effectively, the 1927 dream of a victory by Britain over the US has come true – only now it is under the cover of an EU flag. Perhaps that is the only model to which the EU can ever aspire which might even bring it "victory" in a wider sphere, which might explain why – for all the provocation – the poor little Europeans are so keen for Britain to remain in the EU.

Nevertheless, one does wonder how much of the EU's publicity budget was spent by the European Commission to see six Brits beat the USA.